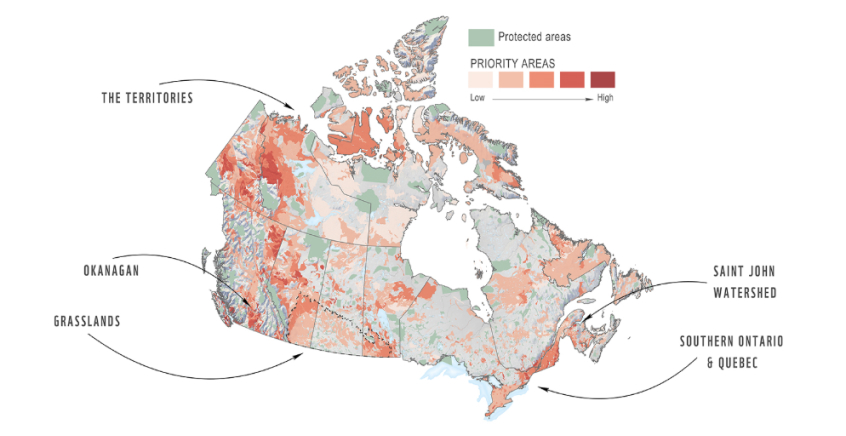

Grizzly bears, barren-ground caribou and wood bison call the Arctic tundra and taiga home. These mostly unprotected habitats range from mountains to valleys, and include Great Slave Lake, the deepest lake in North America, and major free-flowing rivers including the Mackenzie and Liard rivers. The territories have the highest proportion of unprotected physical habitats in the country while facing increasing disturbance from climate change and resource extraction. The Yukon extending into the Northwest Territories has high levels of soil carbon and forest biomass, and important climate refuges. It is also is home to high numbers of at-risk species.

British Columbia’s southern interior is home to unique wildlife like the pallid bat and the desert nightsnake – species that thrive in the region’s hot, dry summers and mild winters. The mix of grasslands, forest, desert-like areas and rich riparian ecosystems provides highly diverse habitats that host many of the province’s at-risk species. Unfortunately, these habitats score poorly in our assessment of ecological representation. Expanding human population, and related road and housing infrastructure, and agriculture development have added pressure to the region where many stressed species have already been extirpated. In addition, the Okanagan is a species hotspot, and contains areas that have high levels of forest biomass and climate refuges.

Grasslands are considered one of the most threatened ecosystems in the world and, for the most part are inadequately or not at all protected. They are home to some of the highest numbers of at-risk species in Canada, including the swift fox and Sprague’s pipit. Over the last century, approximately 80 per cent of the prairie grassland region has been converted for intensive agricultural use. While protection of the grasslands is critical to reversing the decline of our most threatened species, other ecosystems within the prairie provinces contain high densities of soil carbon and forest biomass – which are vitally important to consider as we adopt nature-based solutions to climate change while simultaneously supporting biodiversity.

Southern Ontario and Quebec are highly developed for urban and agricultural needs. Nearly the entire region is either unprotected or very poorly protected, and it is also home to high densities of at-risk species, like the snapping turtle and Jefferson salamander. Increasing privatization of land means that large, intact and connected protected areas are more difficult to implement, which means complimentary conservation options, like habitat restoration, may be necessary to give wildlife the protection they need. In addition to being a hotspot for at-risk species, the region contains some climate refuges – a critical element for species at the northern periphery of their range. Southern Quebec specifically boasts high densities of soil carbon and fair levels of forest biomass.

New Brunswick has the second poorest ecological representation score in Canada, with only one per cent of physical habitats adequately protected. The Saint John River – or Wolastoq – winds across the province as a maze of blind bays, tributaries, lakes and marshlands, providing essential habitat to at-risk wood turtles and shortnose sturgeon. In addition to being home to many at-risk species, some areas of the region contain significant soil and forest biomass carbon stores, and climate refuges. These values, combined with increasing human pressures on the landscape, makes this region a priority for protection.