The beluga of the St. Lawrence estuary is the most southerly whale of its kind. Once considered a prime source of oil, it was harvested in huge numbers. In the 1920s, when cod stocks suddenly declined, fishermen blamed the St. Lawrence belugas. In 1928, the Quebec government handed out rifles and offered a $15 bounty for each beluga killed. Soon after, Quebec authorized aerial bombing of belugas for a few years. By the late 1970s, the population had dropped to a tenth of its historical estimated population size; a hunting ban was implemented in 1979.

Though the St. Lawrence beluga was SARA-listed as Threatened in 2005, a recovery strategy – including a plan to protect vital summer habitat – was repeatedly delayed past the 2007 deadline. It wasn’t until 2012, with the population hovering at approximately 900 whales, that critical habitat was finally identified and the recovery strategy was published. Still, legal protection of the area was delayed until 2016. The St. Lawrence beluga was uplisted to Endangered in 2017. A safe, disturbance-free habitat is essential to the whales, which continue to suffer from contaminants in the food chain, prey-fish availability, entanglement in fishing gear, the effects of climate change, shipping activity and disease.

The piping plover’s pale brown, grey and white feathers make it hard to spot as it forages along retreating waves or nests at the back of wide beaches. When beach-goers and their pets disturb nests, the wary birds abandon them. More humans on beaches, more waterfront cottages and other landscape alterations have battered the plover’s populations in Canada, and in its wintering grounds on the coast in the southern U.S. In the prairies, agriculture is a stressor.

One-third of the global breeding population is found in Canada, but their numbers have dropped by more than a quarter since 1970. The piping plover was listed by SARA as Endangered in 2003. The recovery strategy was finalized in October 2006. In recent years, a small number have returned to the Great Lakes to breed – they were previously extirpated there as a breeding species. Before the plover came under the federal program, conservation efforts to rescue and recover the species were already underway. The education of land owners and beach goers, as well as the introduction of programs to protect nests and young with cage-like predator enclosures, are offsetting some of the declines caused by disturbed habitat. The piping plover has become conservation-dependent.

Barren-ground caribou herds graze and travel across enormous stretches of the Arctic, their journeys taking them between the wintering grounds of the northern boreal forest and their traditional tundra calving grounds, where generation after generation from the same herd return to have their young. More than two million caribou ranged across the Arctic in the early 1990s, but the population total is now estimated to be about 800,000. Several of the largest herds have shrunk by more than 90 per cent from their peak numbers.

In 2016, COSEWIC assessed the barren-ground caribou as Threatened. Climate change is warming the North faster than anywhere else in the world. The higher temperatures bring unseasonal rains that freeze to ground-glazing ice, preventing caribou from reaching lichen and plants they need to survive. At the same time, the altered climate is creating opportunities for industry – mining, tourism and shipping, among others – which could disturb calving grounds or disrupt migration corridors. Managing the harvest becomes difficult when herd numbers are dangerously low. The Government of Nunavut – home to most of the calving grounds – is developing an overarching land-use plan that will set a path for development and conservation in the territory.

This cat-size fox was once at home in grasslands throughout Canada’s southern prairies, of which 80 per cent have now been converted to intensive agricultural use. Along with losing habitat, swift foxes were also caught in traps and died by poisoning by some land-owners. The last sighting of a wild swift fox was in 1938. In 1973, swift foxes were brought from the U.S. for a captive breeding program, and reintroduction of the swift fox into the wild in Saskatchewan and southern Alberta began 10 years later. After being declared extirpated (locally extinct) from Canada in 1978, the swift fox population had grown to 647 in 2009. (However, captive breeding is not always successful: One-third of species reintroduction efforts fail.) While the swift fox status moved from Endangered to Threatened under SARA in 2012, the current population of swift fox only occupies three per cent of its former range.

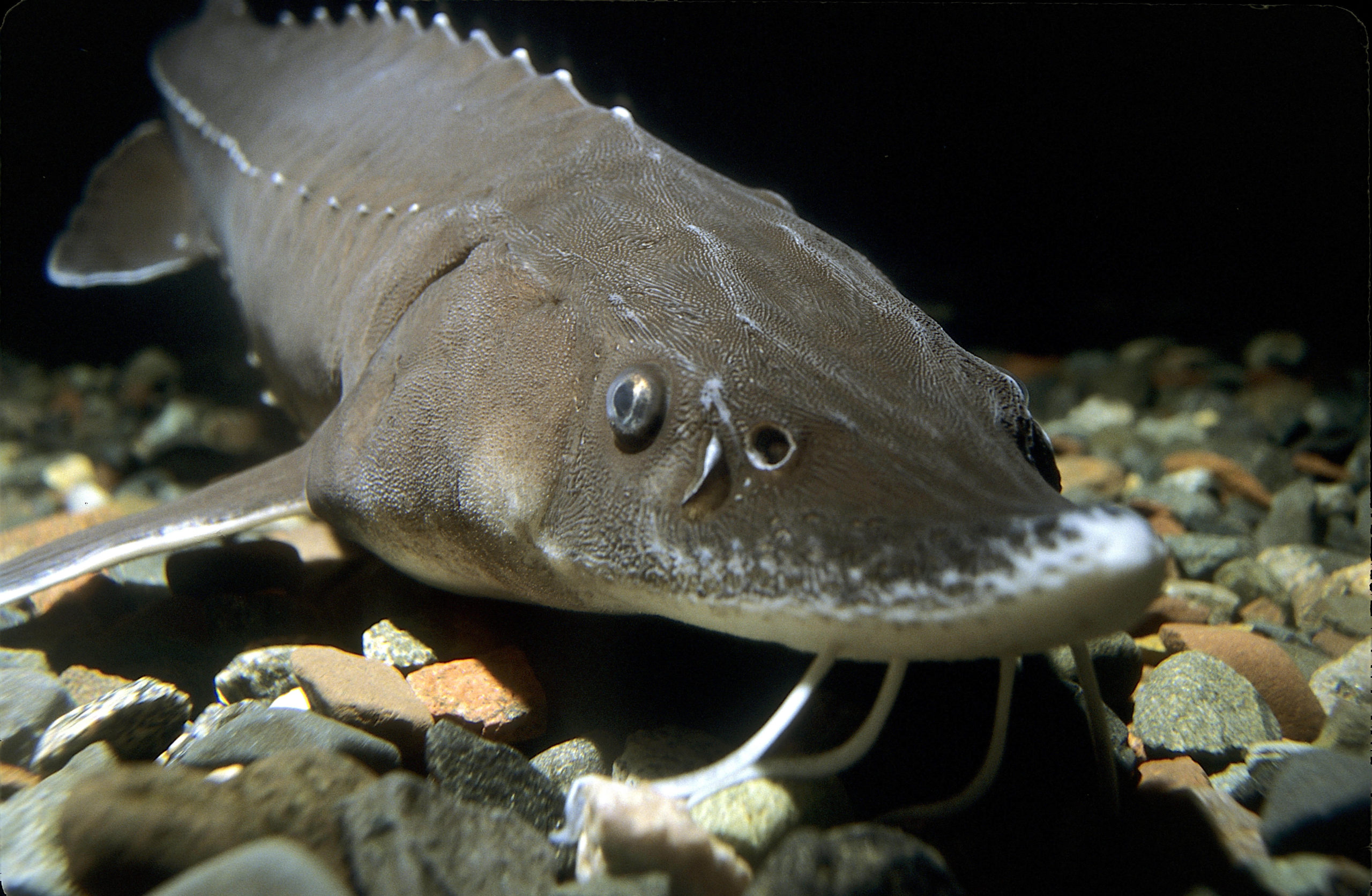

In the shallows of Canada’s large lakes and rivers, enormous lake sturgeon – which can live to 100 years of age – scour the bottom for insect larvae, snails and crayfish. Graceful and shark-like, covered in large bony plates, the country’s largest freshwater fish has, for 200 million years, overcome every threat – until now. After decades of historical commercial overfishing, as well as hydroelectric dam building, lake sturgeon populations have declined and, in some regions, disappeared. They are slow breeders: female lake sturgeon spawn once every four to six years, while males spawn every two to seven years. Eight populations were assessed by COSEWIC as at risk in 2007, including Endangered populations in Nelson River and Western Hudson Bay. The recommendation for listing these populations was put to consultation, which extended until 2012. As of summer 2017, a listing decision has not been made, and lake sturgeon remain without SARA protections. A recent study suggests their economic value for commercial harvesting may be delaying a SARA decision.

© Tim Irvin / WWF-Canada

© Tim Irvin / WWF-Canada